Defining Features of Mid-20th Century Buildings

It’s easy to overlook the more recent past when talking about historic preservation. But the fact is, the mid-20th century saw the rise and fall of a great many architectural styles that we’re already working to preserve today!

We’re going take you on a tour of the architectural styles in use between 1920 and 1980. We’ll discuss the interior and exterior defining characteristics of Art Deco, Post Modern, and many styles in between.

We’re going to cover nine major styles, but keep in mind that there are many sub-styles and informal styles in between!

1927-1940

Art Deco

Art Deco was the first truly international and modern style to come out of Europe. It appeared in France just before World War I, and it acted as a transition between the traditional and modern styles. During this period, architects and artists made a conscious break with past revival precedents, such as Gothic Revival, Colonial Revival, and Greek Revival. They began incorporating many new styles, such as Cubism, Fauvism, and even Chinese, Indian, Persian, and Mayan vernacular styles.

In its heyday, Art Deco represented luxury, glamour, and technological progress. Stylized geometric decorative details using parallel straight lines, zigzags, chevrons and floral motifs are a hallmark of Art Deco style. Its dominance began to wane near the beginning of World War II, and it gave way to more functional and unadorned styles.

LeVeque Tower, Columbus, 1927

Lincoln Theatre, Columbus, 1928

Metropolitan Tower, Youngstown, 1929

Terminal Tower, Cleveland, 1926

Union Terminal/Cincinnati Museum Center, Cincinnati, 1933

1935–1950

Art Moderne

The Art Moderne style enjoyed a brief period of popularity. It was developed just after Art Deco but was soon overtaken by International Style. It’s characterized by rounded edges, curved surfaces, and nautical themes. It was seen as a response to the Great Depression and departed from the ambitious, opulent forms of the Art Deco movement. Instead, Art Moderne buildings feature a more streamlined and austere design.

Streamline Moderne is a sub category of the Art Moderne style. It is inspired by aerodynamic design: curving forms, rounded corners, long horizontal lines, and subdued pastel colors. This style was typically used for transportation-related facilities, such as bus stations, rail terminals, and airports.

Greyhound Bus Terminal, Cleveland, 1948

Kewpee Hamburgers Restaurant, Lima, 1928

Armco Research Building, Middletown, 1937

Colony Theater, Cleveland, 1937

U-Haul/Isaly Dairy, Youngstown, 1941

Original Port Columbus Airport Terminal, Columbus, 1929

Club Moderne, Anaconda, Montana

1932 – 1960

International Style

The International Style was born out of the Bauhaus School of Design Theory in Germany. Its prominent proponents were Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. Inspired and informed by the industrial revolution, it emphasized the functionality of form and shunned ornamentation. It strived to make the building stand on its own regardless of place or context.

“Form follows function” and “less is more” idioms were born out of this style. Its characteristic features were lack of ornamentation, decorative details, or color; use of modern materials such as, concrete, glass curtain walls and metal; rectangular forms; repetitive modular forms; ribbon windows; and open interior spaces.

Pilkington Building, Toledo, 1960

Barcelona Pavilion, Barcelona, Spain, 1928

Seagram Building, NYC, 1958

1955 – 1970

New Formalism

New Formalism emerged as a rejection to the rigid forms of modernism. These buildings were meant to evoke Classical architecture, typically Greek or Roman, and they showcased classical elements, such as symmetrical elevations, columns, highly stylized entablatures, arches and colonnades. This style was used primarily for high-profile cultural, institutional, and civic buildings. Traditional, rich materials were used—like marble and granite—but modern materials like concrete were also employed to create forms such as umbrella shells, waffle slabs, and folded plates. Architect Minoru Yamasaki was a pioneer of this style.

Oberlin Conservatory of Music, Oberlin College, 1963

Pacific Science Center, Seattle, 1962

1950 – 1970

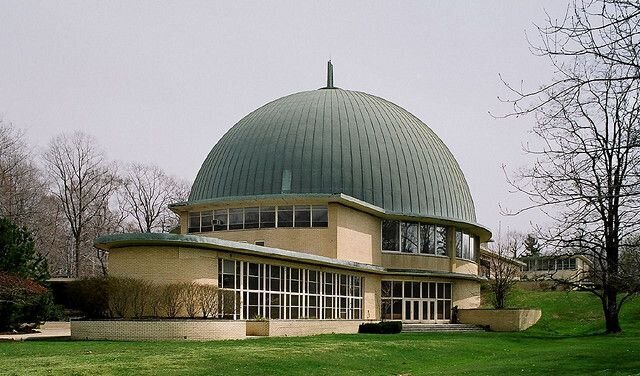

Neo Expressionism

Neo-Expressionism is loosely based on the German Expressionist movement from the early 20th century. It strongly rejected the modern ideals embodied in Miesien buildings, and strived to create unique and individualistic designs. Highly sculptural and personal in style, its goal was to provoke an emotional response. It can be difficult to describe its characteristic features, as Neo-Expressionism does not have a single set of rules or standards to define it. German architect Erich Mendelsohn was a popular advocate of this style.

Park Synagogue, Cleveland Heights, 1947-1953

Pavilion at Bellevue Hill Park, Cincinnati, 1955

1960 – 1970

Futurism / Neo-Futurism

Born in Italy, Futurism was inspired by the Space Age, Atomic Age, and car culture. Its defining features are long dynamic lines, which suggest speed, motion, lyricism, and the future. It often displayed the latest technological innovations. This style was pioneered by architects such as Eero Saarinen.

ASM International World Headquarters, Materials Park, 1959

1933 – 1965

Mid-Century Modern

Perhaps the most popular among the mid-20th century architectural styles is the Mid-Century Modern style. This style, like many others, originated in Europe as part of the Bauhaus movement. It was brought to America by Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—all significant contributors to the Bauhaus Movement in Germany. Its character defining features include flat planes, clean lines, little ornamentation, an emphasis on functionality over form, open floor plans, and large windows for light and views.

An interesting documentary by Arkansas Educational Television Network titled Clean Lines, Open Spaces: A View of Mid-Century Modern Architecture sums up the importance of this style:

“Mid-century modern designs were a by-product of post-war optimism and reflected a nation's dedication to building a new future.”

Our Lady of Peace, Columbus, 1946

Rush Creek Village, Worthington, 1956

St. Columba Cathedral, Youngstown, 1958

Temple Israel, Columbus, 1959

1960 – 1970

Brutalist

The philosophy behind Brutalist designs was to leave behind the over exposure and over transparency of the International Style, and instead embrace mass, solidity, and stability. This style used and celebrated exposed materials, particularly concrete. Its characteristic features include bare façades, no ornamentation, small window openings, and exposed structures on the interior, including exposed MEP systems.

City Hall, Newark, 1967

Crosley Tower, Univ. of Cincinnati, 1969

Ohio History Center, Columbus, 1970

1970s – 1980s

Post Modern

The Post Modern style emerged as a reaction against the austerity, formality, and lack of variety in modern architecture, particularly in the International Style. Post Modernists rejected the International Style’s rigid doctrines, uniformity, and its habit of ignoring the history and culture of the cities where it appeared. They strived to design buildings that were more contextual, original, and interpretive of local culture.

The major proponents of this style were Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, Philip Johnson, Michael Graves, and Peter Eisenman (who designed the Greater Columbus Convention Center). They strongly believed that “buildings should be built for people, and that architecture should listen to them.” The idiom “less is a bore” was coined during this time in reaction to the Miesian philosophy of “less is more.”

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1977

Wexner Center for the Arts, OSU, 1983

Conclusion

The National Historic Preservation Act became law in 1966. Since then, historic architecture has been perceived as something from the 18th and 19th centuries: well-built wood, brick and stone buildings, worthy of preservation. Now that 20th century buildings are fast becoming “historic buildings,” what does that mean for their preservation future? When built, they were affordable, functional, modern buildings, and lacked the “charm” of a quaint Queen Anne or the grandeur of the neo-classical style. Nevertheless, these mid-20th century buildings are a vital part of history. These masterpieces are the legacy of our country’s post-war era, and they deserve to be preserved for future generations. They reflect the values and goals of an important time in U.S. history. And as good stewards of the built history, we need to be sensitive to these historic treasures and advocate for their survival and rejuvenation.